Essay on the Main Theories of Situational or Contingency Approaches!

The leadership approaches discussed so far attributes leadership performance on the basis of certain traits or in terms of leader’s behaviour. The contingency theories propose that an analysis of leadership involves not only the individual traits and behaviour but also a focus on the given situation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The effectiveness of leader behaviour is contingent upon the demands imposed by the situation. The focus is on the situation and not on the leader. Different types of situations demand different characteristics and behaviours because each type of leader faces different situations. A successful leader under one set of circumstances may be a failure under a different set of circumstances. For example, Winston Churchill was considered a successful prime minister and an effective leader of England during World War II. However, he turned out to be much less successful after the war when the situation changed.

The contingency approach defines leadership in terms of the leader’s ability to handle a given situation and is based upon the leader’s skill in that particular area that is pertinent to the situation. This approach can best be described by a hypothetical example developed by Robert A Baron. Imagine the following scenario.

The top executives of a large corporation are going in their limousine to meet the president of another large company at some distance. On the way, their limousine breaks down many miles from any town. Who takes charge of the situation? Who becomes the situational leader?

Not the president or the vice-president of the company, but the driver of the car who knows enough about the motor to get the car started again. As he does the repairs, he gives direct orders to these top echelons of the organizations, who comply. But once the car starts and they arrive at the meeting, the driver surrenders his authority and becomes a subordinate again.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This example makes it clear that in a given situation, the person most likely to act as a leader is the one who is most competent for the situation or for a given group as the case may be. Thus, in defiance of the trait theory, some shy and introvert person may take command of leadership if he meets the group’s requirements under given circumstances.

It must be understood that it would require the leaders to change their behaviour in order to fit the changed situation, if necessary, rather than having to change the situation to suit the leadership behaviour. This means that the leaders must remain flexible and sensitive to the changing needs of the given groups.

While this approach emphasizes that external pressures and situational characteristics and not the personal traits or personality characteristics determine the emergence of successful leaders in performing a given role, it is probably a combination of both types of characteristics that sustains a leader over a long period of time. A” leader is more successful when his personal traits complement the situational characteristics.

According to Szilagyi and Wallace, there are four contingency variables that influence a leader’s behaviour. First, there are the characteristies of the leader himself. These characteristics include the personality of the leader relative to his ability to respond to situational pressures as well as his previous leadership style in similar situations. The second variable relates to the characteristics of the subordinates.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The subordinates are important contributors to a given operational situation. The situation will very much depend upon whether the subordinates prefer a participative style of leadership and decision making and what their motivations in such a situation are. Are the subordinates motivated by intrinsic satisfaction of performing the task well or do they expect other types of extrinsic rewards?

The third factor involves the group characteristics. If the group is highly cohesive, it will create a more cordial situation than if the group members do not get along with each other and the leadership style will vary accordingly.

The fourth situational factor relates to the organizational structure. The organizational structure is the formal system of authority, responsibility and communication within the company.

Factors such as hierarchy of authority centralized or decentralized decision making and formal rules and regulations would affect the leader behaviour. All these factors are diagrammatically shown as follows.

Contingency theories of leadership attempt to account for any relationship between situational factors and leadership effectiveness. There are four such main theories that have been proposed. These are:

A) Fiedler’s Contingency Theory:

The first major contingency model that clearly demonstrated discipline of situational thinking was developed by Fred Fiedler’25‘ in 1967. He proposed a theoretical explanation for interaction of three situational variables which affect the leader effectiveness. These three variables are (1) leader-member relations, (2) task structure and (3) leader’s positional power. These variables determine the extent of the situational control that the leader has.

i. Leader-member relations:

This relationship reflects the extent to which the followers have confidence and trust in their leader as to his leadership ability. A situation, in which the leader-member relationships are relatively good with mutual trust and open communication, is much easier to manage than a situation where such relations are strained.

ii. Task structure:

It measures the extent to which the tasks performed by subordinates are specified and structured. It involves clarity of goals as well as clearly established and defined number of steps required completing the task. When the tasks are well structured and the rules, policies and procedures are clearly written and understood, then there is little ambiguity as to how the job is to be accomplished and hence the job situation is pretty much under control.

iii. Position power:

It refers to the legitimate power inherent in the leader’s organizational position. It refers to the degree to which a leader can make decisions about allocation of resources, rewards and sanctions. Low position power indicates limited authority. A high position power gives the leader the right to take charge and control the situation as it develops.

The most favourable situation for the leader would be when the leader-group relations are positive, the task is highly structured and the leader has substantial power and authority to exert influence on the subordinates.

Fiedler’s Contingency Theory of leadership states that leadership success is determined by these three elements and that the leadership orientation and effectiveness is measured in terms of an attitude scale which measures the leader’s esteem for the “least preferred coworker” or LPC, as to whether or not the person who is least liked by the leader is viewed in a positive or negative way.

For example, if a leader would describe his least preferred coworker in a favourable way with regard to such factors as friendliness, warmth, helpfulness, enthusiasm and so on, then he would be considered high on LPC scale. In general, a high LPC score leader is more relationship oriented and a low LPC score leader is more tasks oriented.

A high LPC leader is most effective when the situation is reasonably stable and requires only moderate degree of control. The effectiveness of a high LPC leader stems from motivating group members to perform better and be dedicated towards goal achievement. A low LPC leader would exert pressure on the subordinates to work harder and produce more.

These pressures would be directed through organizational rules, policies, procedures and expectations with regard to performance. The low LPC leader would be highly effective when situational control is either very low or very high. Under conditions of low situational control, groups need considerable guidance and direction to accomplish their tasks. In such situations a task oriented leader will be more successful.

Similarly, under conditions of high situational control, the conditions are very good and successful task performance is practically assured. This requires very little interference by low LPC leaders, which is appreciated by the subordinates thus enhancing the leader’s effectiveness.

This relationship of leadership effectiveness and the degree of situational control is shown as follows:

1. Low LPC leaders are highly effective under low situational control.

2. High LPC leaders are highly effective under moderate situational control.

3. Low LPC leaders are highly effective under high situational control.

One of the basic conclusions that can be drawn from Fiedler’s contingency model is that a particular leadership style may be more effective in one situation and the same style may be totally ineffective in another situation and since a leadership style is difficult to change, the situation should be changed to suit the leadership style.

The situation can be made more favourable by enhancing relations with the subordinates, by changing the task structure or by gaining more formal power which can used to induce a more conducive work setting based upon personal leadership style.

Fiedler and his associates also developed a leadership training programme known as “Leader Match”, giving the manager some means and authority to change the situation so that it becomes more compatible with the leader’s LPC orientations. The programme shows the trainees how to compute scores for LPC and situational factors and then how to alter the situation to match the trainees’ LPC.

B) Path-Goal Theory:

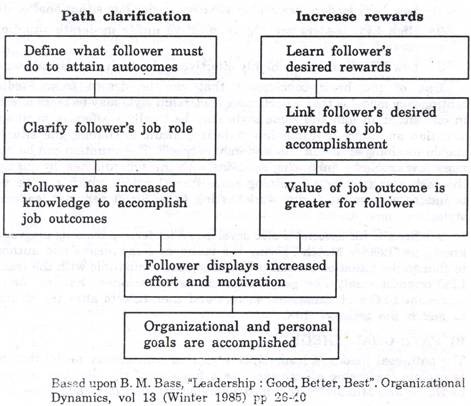

The path-goal theory of leadership is another contingency model that tries to explain leadership effectiveness as a function of the situation. Proposed by House and Mitchell, this model emphasizes that the leader’s behavior be such as to complement the group work setting and group aspirations so that it increases the subordinate’s motivation to attain personal and organizational goals.

The leader sets up clear paths and clear guidelines through which the subordinate can achieve these goals and assists them in such achievement. This will make the leader’s behaviour acceptable and satisfying to the subordinates since they see the behaviour of the leader as an immediate source of satisfaction or as a source of’ obtaining future satisfaction.

To motivate workers, the leader would:

i. Recognize subordinate needs for outcomes over which the leader has some control.

ii. Arrange for appropriate rewards to his subordinates for goal achievement.

iii. Help subordinates in clearly establishing their expectations.

iv. Demolish as far as possible any barriers in their path of goal achievement.

v. Increase opportunities for personal satisfaction which are contingent upon satisfactory performance.

The leader’s role in the Path-Goal model is shown in the following diagram.

The Path-Goal model takes into consideration the different types of leadership behaviour. There are four such leadership styles that would support this approach depending upon the nature of the situation. These are:

i) Directive:

Directive leadership is the style in which the leader provides guidance and direction to subordinates regarding job requirements as well as methodology for job accomplishment. This style is required when the demands of the task on hand are ambiguous and not clearly defined. However, when the task is inherently clear or clarification is otherwise available, then a high level of directive leadership is not required and may, in fact, impede performance.

ii) Supportive:

Supportive leadership is a style in which the leader is concerned with the needs and well-being of his subordinates. The leader is friendly and approachable and treats his subordinates as equals. This approach has the most positive effect, specifically on the satisfaction of those followers who are working on unpleasant, stressful or frustrating tasks that are highly repetitive.

iii) Achievement-oriented:

This type of support helps the subordinates to strive for higher performance standards and increases confidence in their ability to meet challenging goals. This is especially effective for followers who have clear-cut and non-repetitive assignments.

iv) Participative:

This leadership approach encourages subordinate’s participation in the decision making process. The leader solicits subordinate’s suggestions and takes the suggestions into consideration before making decision.

C) Situational Leadership Theory (SLT):

The third contingency approach is the situational leadership theory. Developed by Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard, it was originally known as the “Life-cycle-theory” and it focuses on the “maturity of the followers as a contingency variable affecting the style of leadership.”

The maturity of the subordinates can be defined as their ability and willingness to take responsibility for directing their own behaviour in relation to a given task. The level of such maturity would determine the leader’s emphasis on task behaviour (giving guidance and direction) and relationship behaviour (providing socio-emotional support).

“Task behaviour” can be defined as the extent to which the leader engages in specifying and clarifying the duties and responsibilities of an individual or a group. Such behaviour includes telling people what to do, how to do it, when to do it, where to do it and who is to do it. Task behaviour is characterized by one-way communication from the leader to the follower and this communication is meant to direct the subordinate to achieve his goal.

Similarly, “relationship behaviour” is defined as the extent to which the leader engages in two-way or multi-way communication. Such behaviour includes listening, facilitating and being supportive.

“Maturity” is the crux of situational leadership theory it has been defined previously as reflecting the two elements of ability and willingness on the part of the followers. Ability is the knowledge, experience and skill that an individual or a group has in relation to a particular task being performed and the willingness refers to the motivation and commitment of the individual or the group to successfully accomplish such given task.

The style of leadership would depend upon the level of maturity of the followers. The following diagram suggests four different styles of leadership for each stage of maturity and a particular style in relationship to its relative level of maturity is considered to be the “best match.”

These various combinations of leadership styles and levels of maturity are explained in more detail as follows:

(S1). Telling:

The “telling” style is best for low follower maturity. The followers feel very insecure about their task and are unable and unwilling to accept responsibility in directing their own behaviour.

Thus they require specific instructions as to what, how and when to do various tasks so that a directive leadership behaviour is more effective in such a situation. The leadership style involves high task behaviour and low relationship behaviour.

(S2). Selling:

The “selling” style is most suitable where followers have low to moderate level of maturity. The leader offers both task direction as well as socio-emotional support for people who are unable but willing to take responsibility. The followers are confident but lack skills. It involves high task behaviour and high relationship behaviour. It combines a directive approach with reinforcement for maintaining enthusiasm.

(S3). Participating:

This leadership approach also involves high relationship behaviour as well as high task behaviour and is suitable for followers with moderate to high level of maturity where they have the ability but not the willingness to accept responsibility, requiring a supportive leadership behaviour to enhance their motivation. It involves sharing ideas and maintaining two-way communication to encourage and support the skills that the subordinates have developed.

(S4). Delegating:

Here the employees have both the job maturity as well as psychological maturity. They are both able and willing to be accountable for their responsibility toward task performance and require little guidance and direction. It involves low relationship and low task behaviour and it is appropriate for the leader to use delegating style.

The situational leadership requires that leaders should be flexible in choosing a leadership style and that they attend to the demands of the situation as well as the feelings of the followers, and adjust their styles with the changing levels of maturity of the followers so as to remain consistent with the actual levels of maturity.

D) Vroom-Yetton Model:

One of the major tasks performed by leaders is making decisions. This model is normative in nature for it simply tells leaders how they should behave in decision making. The focus is on the premise that different problems have different characteristics and should therefore be solved by different decision techniques. The effectiveness of the decision is a function of leadership style which ranges from the leader making decisions himself to a totally democratic process in which the subordinates fully participate depending upon the contingencies of the situation which describe the attributes of the problems to be dealt with.

After careful study of available evidence, Vroom and Yetton concluded that leaders often adopt one of the five distinct methods for making decisions, ranging from totally individualized decision making by the leader on one extreme to totally participative decision making style at the other extreme. These styles are described as follows. (A stands for autocratic, C for consultative, and G for group).

AI:

The leader or manager makes the decision himself and his decision is based upon whatever information or facts are available to him.

AII:

The leader or manager makes the decision himself but gets all the information needed personally from his subordinates. The role of the subordinates is limited to input of data only. They do not take any part in the decision making process. They may not even know what the problem is. Even if they know about the problem, they have no input in generating or evaluating alternative solutions.

CI:

While in All style, the manager simply gets the information from his subordinates, in CI style, he consults his subordinates, who are expected to be involved with the outcome of the decision or who are knowledgeable about certain elements of the problem.

He consults them individually, getting their ideas and suggestions without bringing them together as a group. The manager may or may not take their suggestions into consideration when making the final decision.

CII:

In this style of decision making, the manager meets with his subordinates as a group, instead of meeting with them on an individual basis, and gets their ideas and suggestions relative to the problem. He makes the decision unilaterally and this final decision may or may not reflect their input.

GII:

This is a participative style of decision making. The problem is shared with the group and solutions and alternatives are generated and evaluated together. The final solution is decided by the group by consensus and such solution is implemented.

Vroom and Yetton propose that leaders should attempt to select the best approach out of these five approaches by asking several basic questions about the situations in which they find themselves. These questions relate primarily to two variables, namely, the “quality of the decision” and “acceptance of the decision.”

The “quality of the decision” refers not only to the importance of the decision to performance of the subordinates relative to organizational goals but also whether such performance is optimal in nature and whether all relative inputs had been considered during decision making process.

The “decision acceptance” refers to the degree of commitment of the subordinates to the decision. Whether the decision has been made by the leader himself or with the participation’ of subordinates, it must be accepted whole heartedly by those who are going to implement it.

The decision itself has no value unless it is efficiently and correctly executed. When subordinates accept a decision as their own, they will be more committed to implementing it effectively.

The basic questions relating to the decision quality and decision acceptance are proposed by Rao and Narayana. There are seven such questions. The first three questions relate to the quality of the decision and the rest of the four questions protect the decision acceptance by the subordinates. These questions are:

i. Is there a quality requirement such that one solution is likely to be more rational than another?

ii. Is the problem structured?

iii. Does the manager have sufficient information to make a high quality decision?

iv. Is acceptance of decision by subordinates critical to effective implementation?

v. If the decision was to be made unilaterally by the manager, is it reasonably certain that such a decision would be accepted by the subordinates?

vi. Do the subordinates share the organizational goals to be achieved in solving the problem?

vii. Is conflict among subordinates likely in preferred solutions?

On the basis of responses to these questions, some rules can be established which would guide the leader in selecting a decision making style which would be most appropriate to the situation. By applying these rules, leaders can eliminate such decision making strategies that are likely to prove ineffective. These rules are described as follows.

Rules Regarding Decision Quality:

i. If the manager does not have sufficient information or expertise to solve the problem and the quality of the decision is important, then eliminate the autocratic style.

ii. If the quality of the decision is important and subordinates are not likely to make the right decision, rule out the participative style.

iii. If the quality of the decision is important and the problem is unstructured and complex, eliminate the autocratic leadership style.

Rules Regarding Decision Acceptance:

i. If acceptance by subordinates is crucial for effective implementation, eliminate the autocratic style.

ii. If acceptance is crucial and the subordinates hold conflicting opinions over the means of achieving some objectives, eliminate autocratic style:

iii. If acceptance by subordinates is more important than the quality of the decision, use the most participatory style.

iv. If acceptance is critical and autocratic decisions are not likely to be accepted by subordinates and if such subordinates are highly motivated to achieve the organizational goals, and then use a highly participative style.

While Vroom-Yetton model establishes some guidelines which are useful in selecting the most effective decision making style, such a selection is a function of time available for making the decision.

Many situations develop in the form of a crisis where immediate and fast actions have to be taken requiring quick decision. The subordinates must understand that their participation in decision making is very time consuming and under certain situations the delay in decision making could be very dangerous.

Accordingly, as long as the decision is complementary to the subordinate’s aspirations and organizational goals, an individualistic decision making style is more desirable if decisions have to be made under time constraints.

![clip_image002[4] clip_image002[4]](https://www.shareyouressays.com/wp-content/uploads/hindi/4-Main-Theories-of-Situational-or-Contin_8552/clip_image0024_thumb.jpg)